CONSTANTIAM hic appello, rectum & immotum animi robur non elati externis aut fortuitis, non depressi [I term CONSTANCY an upright and stationary force of mind, neither elated nor cast down by external accidents].

Justus Lipsius, De Constantia Libri Duo (Antwerp: 1584), p.10

EDWARD. Father, this life contemplative is heaven! O that I might this life in quiet lead.

Christopher Marlowe, Edward II, IV.vii.20-1

The political arena – indeed public life generally – was a dangerous place in Marlowe’s time, particularly in the war-torn environment of northern Europe. During the 1570s and 1580s, certain thinkers began to develop ideas of contemplative retirement as an intellectual refuge from external jeopardy. Such notions often went together with a philosophy of self-reliance, as in Lipsius’s De Constantia (1584), or subjective autonomy, as in the famous Essais of Montaigne (first published 1580).

Marlowe’s imaginative works also exhibit an interest constructing blissful and secure refuges, often as spaces suited to a scholar’s ‘wit’ – but were such impulses connected to the revival of neo-Stoicism in late sixteenth-century Europe? The video, above, has me offering preliminary thoughts on this question, while below there are some highlights of the project’s research in this field.

- Pierre la Primaudaye’s French Academie

Pierre la Primaudaye’s Academie Francaise, first published in 1577 and first translated into English in 1586 by the strongly Protestant Thomas Bowes, anticipated the more developed neo-Stoicism of Lipsius and Montaigne. It is notable for its setting, often thought to have inspired Shakespeare’s Love’s Labours Lost (?1594): four French noblemen retire from the religious wars besetting France to discuss the ends of human life.

La Primaudaye was in some respects a conventional thinker, often rehearsing what are little more than elegant Aristotelianisms – but occasionally his ideas are more uptodate. His sections on politics, for example, borrow from the recently published political theories of Jean Bodin a concept of ‘sovereignty’; you can find out more about Bodin elsewhere on this website.

2. Lipsius’s De Constantia (1584).

The De Constantia of Justus Lipsius is sometimes considered the only ‘pure’ work of Renaissance neo-Stoicism, offering an account of inner fortitude both tempered to the war-torn Netherlands of the 1580s, and subtly merging ancient Stoic with Christian ideas.

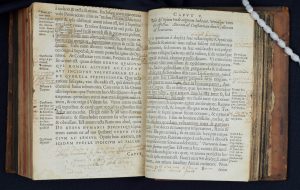

The image below is from a copy of what is probably the 1586 edition of Lipsius’s work (it is missing its title page), now in the Fellows Library of Jesus College, Oxford, shelfmark R.7.9(7) Gall. An early modern reader has added extensive extracts from John Stradling’s English translation of 1594, as well as some remarks, in Latin – and on a slightly different occasion – on the text’s rhetorical devices (e.g. ‘similitudo’ [a simile], in the right hand margin ).

Both types of annotation reflect an interest in Lipsius’s compressed but vividly expressive prose style, which is also suggested by annotations of other early modern copies. The neo-Stoic subject of the late sixteenth century, one might argue, was consciously a work of literary as well as psychological self-fashioning.